Testing approaches in Ruby

The first part half of this post will discuss an overview of different testing techniques and approaches that you can use within your development cycle to improve code quality. Followed by some useful RSpec snippets and patterns when leveraging RSpec for testing your Ruby code.

Why test?

There's lots of reasons to write tests as part of the development cycle of software, including but not limited to:

- Encourages the developer to think about edge-cases and fix bugs

- Catch regression issues before your users find them

- Invaluable when upgrading third-party libraries

- Useful when onboarding new developers/maintaining old code

- Traceability to requirements

Types of tests

Different testing frameworks use different terminology, but in general the types of tests that a developer will often include the following concepts

Unit tests

Unit tests, or component testing, will test easily separable functions/modules in isolation. These tests are fast to run, and often fast to write. Often useful when testing standalone algorithms and objects with complex business logic which must be verified thoroughly.

calculator_result = calculator.add(2, 5)

expect(calculator_result).to eq(7)Integration tests

Often done after unit tests are developed. These tests will verify that multiple modules work together in harmony. These set of tests can often be slow as multiple levels of code and abstraction will execute, potentially making database calls etc.

result = some_complex_function_with_database_calls()

expect(result).to eq({ ... })Functional / System / end-to-end tests

These set of tests will ensure that the full system works as expected from a user's perspective. This often requires replicating real user actions through a real browser.

There are lots of tools to choose from here, such as Capybara, a Ruby library for testing web applications via a browser:

require 'feature_helper'

RSpec.feature 'Blog management' do

scenario 'Successfully creating a new blog' do

visit '/blogs'

fill_in 'blog_title', with: 'My Blog Title'

fill_in 'blog_text', with: 'My new blog text'

click_on 'Save Blog'

expect(page).to have_selector('.blog--show')

expect(page).to have_content('My Blog Title')

expect(page).to have_content('My new blog text')

end

endYou may even encounter Cucumber or Gherkin syntax tests, which is a way of implementing human readable user stories in code:

Scenario: User adds their first blog post

Given the user has no blog posts

When the user creates a new blog post with the title "My blog title" and content "My blog text"

Then the home page should contain the following blogs:

| id | title | content |

| 1 | My blog title | My blog content |These stories will take the format of Given / When / Then:

Given- Pre-requisite state that the system must be in (Arrange)When- When the user performs an action (Act)Then- Verify the output of the system (Assert)

Behind the scenes these human readable strings would be implemented programmatically within your language of choice. A runtime library would then glue the various steps together to complete the test:

When /^the user creates a new blog post with the title "([^"]*)" and content "([^"]*)"$/ do |title, content|

visit '/blogs'

fill_in 'blog_title', with: title

fill_in 'blog_text', with: content

click_on 'Save Blog'

endPerformance

Testing non-functional requirements, such as how many requests per second an API can handle, or even how fast a particular particular algorithm or datastructure is.

benchmark-ips is a useful library which will run a code snippet multiple times, comparing the relative performance of different implementations:

require 'benchmark/ips'

Benchmark.ips do |x|

x.report('implementation 1') do

# ...

end

x.report('implementation 2') do

# ...

end

x.compare!

endThe library will also figure out how many times to run the code to get interesting data without needing to tweak the loop count manually:

Warming up --------------------------------------

implementation 1 1.429M i/100ms

implementation 2 1.290M i/100ms

Calculating -------------------------------------

implementation 1 13.839M (± 3.7%) i/s - 70.021M in 5.066857s

implementation 2 14.529M (± 6.1%) i/s - 73.552M in 5.082248s

Comparison:

implementation 2: 14528559.1 i/s

implementation 1: 13839063.9 i/s - same-ish: difference falls within errorWhich tests should I write?

Just as there's multiple ways to structure a piece of software, with different advantages and trade-offs, there is multiple ways to structure your test suite.

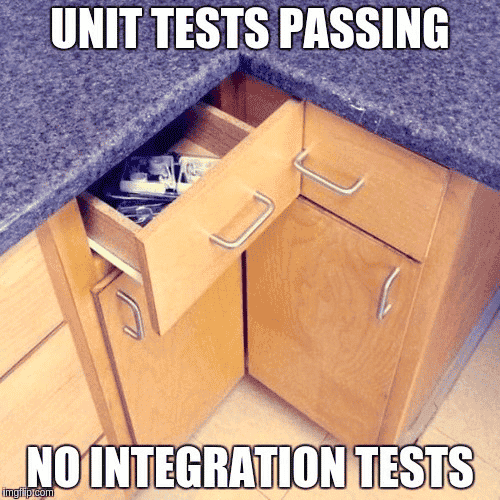

Unit tests are fast to run, and are often initially fast to write. Unfortunately as they often stub/mock external dependencies, they may not provide the reassurance that the system will work as a whole. For this reason, it could be suggested that integration tests provide the most for benefit for their relative cost. Whilst end-to-end tests will ensure that user stories work as expected, they can often be the most flakey.

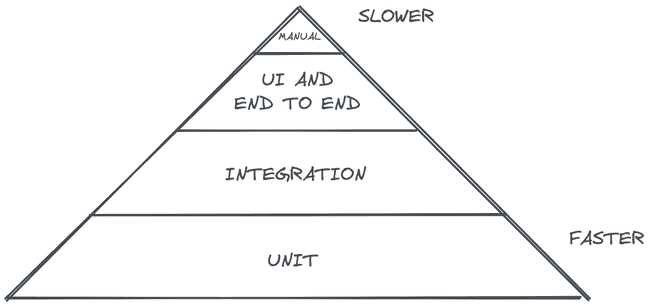

Testing pyramid

You may consider writing a lot of unit tests, which are fast to run. Followed by less integration tests, and an even smaller amount of UI/End to End tests.

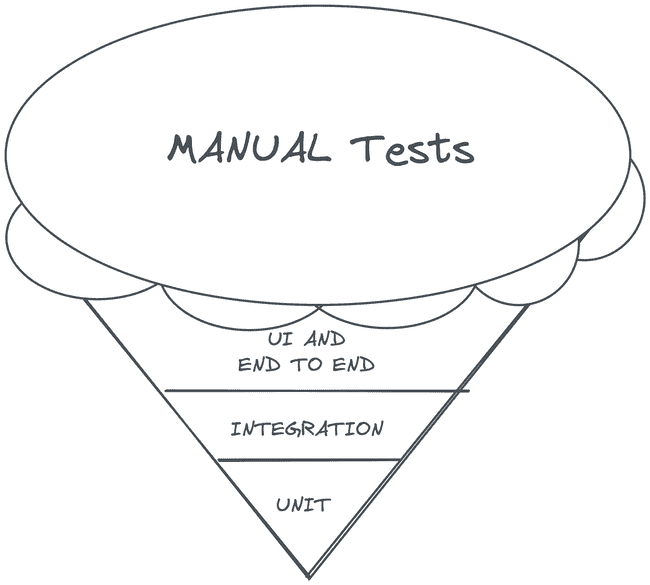

Testing ice-cream cone

The testing ice cream cone can be considered an anti-pattern, as it is often an indication that the manual testing could be migrated to faster automated testing:

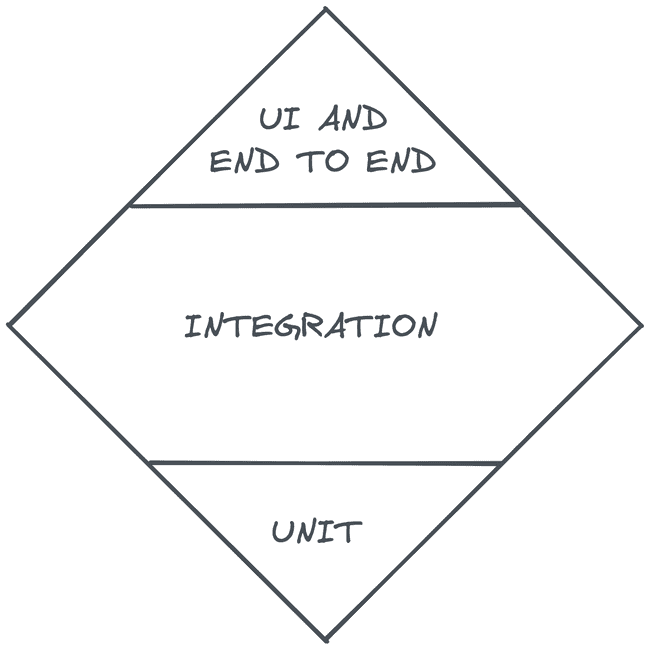

Testing diamond

An alternative approach is to favor integration tests as a good middleground solution, balancing the trade-offs between test speed and usefulness:

Test structure

Arrange-Act-Assert

In general tests should follow the format of:

- Arrange all necessary preconditions and input

- Act upon the object or method

- Assert that the expected results have occurred

For example:

# Arrange - insert values into the database, mock library calls, etc.

allow(external_library).to receive(:some_method).and_return(:mocked_value)

Database::User.insert(...)

# Act

result = subject.create_blog(title: '...', content: '..')

# Assert

expect(result.title).to eq('...')

expect(result.content).to eq('...')Red-Green-Refactor

A common workflow as part of Test-driven development (TDD) is the concept of red-green-factor, summarised as:

- Red - Write automated tests

- Green - Write the least amount of code to make tests pass

- Refactor - Restructure/improve the code quality

This pattern will be repeated until the feature is successfully developed:

Coverage tools

These tools are useful for highlighting code paths that are not tested, for instance this is the output of simplecov:

Mutation testing

Mutation involves rewriting the code under test in various ways, called mutant. For instance by rewriting predicate expressions and running the test suite again:

# original code

if a && b

c = 1

else

c = 0

end

# mutant generated, and test suite-rerun

if a || b

c = 1

else

c = 0

endThe existing test suite must be able to identify this new mutant code. If it does not, then the test coverage is not sufficient enough - or the implementation could be simplified.

Other mutations include:

- Statement deletion

- Replacing booleans, i.e. true to false

- Modifying comparison operators from

>to>=or== - etc

Tools such as mutant can be used for this

Property based testing

When a developer is writing unit tests, a common approach is to:

- Decide on a finite set of test data, i.e. 1-2 happy paths, 1-2 failure paths

- Arrange - Create the input

- Act - Call the function with the input

- Assert - Verify the result

Alternatively; From the lands of functional programming - tools such as Haskell's QuickCheck allow tests to be developed by asserting properties that the function under test must honor. This allows for the test library to choose arbitrary inputs to your test which follow the set pre-conditions, and for the post-conditions to be verified afterwards.

- Declare a specification of the input data

- Let the testing library choose arbitrary input data

- Verify the post conditions hold true for the result

An example with ruby-prop_check:

include PropCheck::Generators

# testing that Enumerable#sort sorts in ascending order

PropCheck.forall(array(integer)) do |numbers|

sorted_numbers = numbers.sort

# Check that no number is smaller than the previous number

sorted_numbers.each_cons(2) do |former, latter|

raise "Elements are not sorted! #{latter} is < #{former}" if latter < former

end

endRSpec Cheat sheet

I recommend reading through betterspecs which curates a list of the current best practices for writing RSpec tests.

Example

RSpec provides a domain specific language for writing tests. For unit tests you will want to use the real class name in the top level describe to signify the class that you are wishing to test. This will allow RSpec to load the class that is being tested, as well as provide access to useful helper methods later:

# If you're testing a class in isolation

RSpec.describe SomeClass do

# ...

endFor system/end-to-end tests there will be a readable string for the describe argument, instead of the Ruby class that is being tested:

# If you're writing system/end-to-end tests

RSpec.describe 'Blog management system' do

# ...

endConventions

If you were wishing to test a class such as:

class Person

def self.class_method

# ...

end

def instance_method

# ...

end

endIf you're testing an instance method:

# using the # prefix for instance methods

describe '#instance_method' do

# ...

endIf you're testing a class method:

# Using the `.` prefix for class methods

describe '.class_method' do

# ...

end

# Sometimes you will see the `::` prefix used

describe '::class_method' do

# ...

endIf you wish to test a method, under a combination of different contexts and variations:

# start the contexts with `when...`, `with ...`, `without... `

describe '#instance_method' do

context 'when the user has permissions' do

# ...

end

context 'when the user does not have permissions' do

# ...

end

endUtility methods

Given the following code snippet:

RSpec.describe Person do

# ...

endThe following methods are available for use:

described_classrefers to the Person classsubjectwill refer to Person.new by default

Assertions / Matchers

When we write unit tests in the format:

calculator_result = calculator.add(2, 5)

expect(calculator_result).to eq(7)It's worth noting that this is actually just a bunch of function calls. For instance eq is just a function call:

calculator_result = calculator.add(2, 5)

expect(calculator_result).to(eq(7))RSpec provides multiple out of the box matchers such as:

eqincludematchbe_within(delta).of(expected)match_array- ... and more!

It is also possible to write custom matchers:

it 'should take a screenshot' do

screenshot = subject.screenshot

expect(screenshot).to equal_image(expected_screenshot)

endThe following snippet shows an example of registering a new matcher with RSpec which you can use in your test:

RSpec::Matchers.define :equal_image do |expected_path|

match do |actual_path|

expected_pixels = pixels_for(expected_path)

actual_pixels = pixels_for(actual_path)

expect(expected_pixels == actual_pixels).to be true

end

# @param [String] path The file path to the image

def pixels_for(path)

image = Magick::Image.read(path).first

image.export_pixels_to_str(0, 0, image.columns, image.rows)

end

endMatchers for complex structures

RSpec's matchers can be used within arbitrary data structures to test complex scenarios:

expected_error_response = {

error: {

code: -32000,

data: hash_including({

backtrace: include(a_kind_of(String))

}),

message: 'Application server error: This module does not support check.'

},

id: 1

}

expect(json_response).to include(expected_error_response)Fixing flakey tests

Tests that are unreliable, and fail non-deterministically, can be referred to as flakey tests.

Order dependent tests

By default tests should run in a random order, but the module author may assume that they run sequentially. Sometimes a test suite can fail due to a series of tests mutating external state, and the order in which the tests run impacts the overall test result.

The tests will be shuffled randomly based on an initial seed, which will be output to the stdout that ran the test suite:

Randomized with seed 1234Similar to git bisect, RSpec supports the --bisect flag. We can then run the test suite again, supplying the seed value:

rspec --seed 1234 --bisectThis will then bisect the test suite until it finds the combination of tests which leads to the failure:

Bisect started using options: "--seed 1234"

Running suite to find failures... (0.16755 seconds)

Starting bisect with 1 failing example and 9 non-failing examples.

Checking that failure(s) are order-dependent... failure appears to be order-dependent

Round 1: bisecting over non-failing examples 1-9 .. ignoring examples 6-9 (0.30166 seconds)

Round 2: bisecting over non-failing examples 1-5 .. ignoring examples 4-5 (0.30306 seconds)

Round 3: bisecting over non-failing examples 1-3 .. ignoring example 3 (0.33292 seconds)

Round 4: bisecting over non-failing examples 1-2 . ignoring example 1 (0.16476 seconds)

Bisect complete! Reduced necessary non-failing examples from 9 to 1 in 1.26 seconds.

The minimal reproduction command is:

rspec ./spec/calculator_10_spec.rb[1:1] ./spec/calculator_1_spec.rb[1:1] --seed 1234Ignoring array order

Tests can sometimes fail due to an array being returned in a different order. For instance, retrieving values from a database which are not explicitly ordered. To fix this, either fix the implementation to be deterministic, or update the matcher:

expect([1, 2, 3]).to eq([1, 2, 3]) # pass

expect([2, 3, 1]).to eq([1, 2, 3]) # fail

expect([2, 3, 1]).to match_array([1, 2, 3]) # pass

expect([1, 2, 3]).to contain_exactly(1, 2, 3) # pass

expect([:a, :c, :b]).to contain_exactly(:a, :c ) # failThe RSpec matcher output will make it clear what has failed:

Failure/Error: it { is_expected.to contain_exactly(1, 2, 1) }

expected collection contained: [1, 1, 2]

actual collection contained: [1, 2, 3]

the missing elements were: [1]

the extra elements were: [3]It works on my machine

In some scenarios your test suite may fail on CI, but tests will pass locally on a development machine. This can be caused by environment differences between CI and your local environment.

It's worth verifying the file names of paths within your codebase, as well as the file name that is actually stored on disk, as Linux has a case sensitive-file system. Any misalignment here could cause issues on a Linux environment, but work for a Mac/Windows machine.

Another difference is locale environment variables which configure the language, country, and character encoding settings for your machine. It's worth verifying these values via the locale command:

$ locale

LANG="en_GB.UTF-8"

LC_COLLATE="en_GB.UTF-8"

LC_CTYPE="en_GB.UTF-8"

LC_MESSAGES="en_GB.UTF-8"

LC_MONETARY="en_GB.UTF-8"

LC_NUMERIC="en_GB.UTF-8"

LC_TIME="en_GB.UTF-8"

LC_ALL=Testing side-effects

RSpec provides a nice matcher for the verifying that a method call has changed state:

expect { Models::User.delete_All }.to change { Models::User.count }.from(0).to(1)

expect { Models::User.delete_All }.to change { Models::User.count }.by(1) # Often preferredTime travel

Although it's best practice to test functions in isolation without needing to mock out time, it can be useful. For this reason Timecop can be used which is a gem providing "time travel" and "time freezing" capabilities, making it dead simple to test time-dependent code. It provides a unified method to mock Time.now, Date.today, and DateTime.now in a single call.

before(:each) do

Timecop.freeze(Time.local(2008, 9, 5, 10, 5, 30))

end

after(:each) do

Timecop.return

endTimecop can also time travel to new points in time during a test run:

expect(joe.mortgage_due?).to be false

# move ahead a month and assert that the mortgage is due

Timecop.freeze(Date.today + 30) do

expect(joe.mortgage_due?).to be true

endData driven tests

Data-Driven tests can be useful to generate multiple test permutations:

[

nil,

false,

'',

' '

].each do |input|

context "when the input is #{input}" do

it 'should return false' do

expect(subject.verify(input)).to eq(false)

end

end

endAvoid testing real services

If possible, you should avoid testing against real services. We do this to ensure the speed and stability of the testing framework. For instance, if the remote service dies - we would not want that to impact test runs locally or in CI environments.

Ways to avoid this include mocking external dependencies:

before(:each) do

allow(third_party_library).to receive(:get_user).with(id: 1).and_return(mock_user)

endOr use a tool such as VCR which can record the initial HTTP calls with a web service, and save the files locally. Future test runs will make use of the locally saved test files and not make real HTTP requests:

require 'vcr'

VCR.configure do |c|

c.cassette_library_dir = 'spec/cassettes'

c.hook_into :webmock

c.configure_rspec_metadata!

endWith a unit test:

require 'spec_helper'

def make_http_request

Net::HTTP.get_response('localhost', '/', $server.port).body

end

RSpec.describe 'VCR example group metadata', :vcr do

it 'records an http request' do

expect(make_http_request).to eq('Hello')

end

endWhen the test first runs this will generate a cassette file which is saved to disk for future use:

---

http_interactions:

- request:

method: get

uri: http://example.com/foo

body:

encoding: UTF-8

string: ""

headers: {}

response:

status:

code: 200

message: OK

headers:

Content-Length:

- "5"

body:

encoding: UTF-8

string: Hello

http_version: "1.1"

recorded_at: Tue, 01 Nov 2011 04:58:44 GMT

recorded_with: VCR 2.0.0There is also TCR for recording TCP/binary requests. This file is not stored in a human readable format like VCR's yaml output. Instead it uses Ruby's Marshal library - which is not human readable and may suffer from deserialization attacks. This would especially be a concern if malicious pull requests were to be accepted as part of open source projects.

Configuration example:

TCR.configure do |config|

config.hook_tcp_ports = [5902]

config.format = 'marshal'

config.cassette_library_dir = File.join(FIXTURES_ROOT, 'tcr')

endWiring up the casette functionality to our test suite:

around(:each) do |example|

cassette_name = test_name_for(example)

TCR.use_cassette(cassette_name) do

example.run cassette_name

end

end

it 'should take a screenshot' do

screenshot = subject.screenshot

expect(screenshot).to equal_image(expected_screenshot)

end